What has ESA ever done for us?

Everybody has heard of NASA and could list some of their greatest achievements. Less familiar are the successful projects of the European Space Agency (ESA) and this is a situation which our August speaker Paul Hill was keen to put right. Here are some of the unmanned projects he spoke about, starting with the most recent. (I say “unmanned” as Tim Peake was, of course, an ESA astronaut)

The Rosetta mission, about which there has been so much publicity since its rendezvous with Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and the landing of Philae on that comet, began as a joint ESA and NASA project. After various changes of plans mainly driven by financial considerations, NASA had withdrawn. I wonder how many people would still assume that it was NASA’s rather than ESA’s mission and not realise that it was controlled from ESA’s centre at Darmstadt and not Houston. Not only was Rosetta the first object to be put into orbit round a comet and not only was Philae the first object to make a soft landing on a comet, the mission had fulfilled several other tasks on its long, long journey as it used slingshots to pick up energy before it reached its comet. These included observing NASA’s Deep Impact Impactor deliberately crashing into the comet Tempel-1, imaging Mars during a fly-past and having a close encounter with two asteroids as it crossed the asteroid belt.

One of ESA’s earlier achievements was also linked to a comet, Halley’s comet. The space probe Giotto was part of an international group of 5 probes sent to study it during its return to the inner Solar System in 1986. The group was called Halley’s Armada and did not include anything from NASA which was in no position to participate after the Challenger disaster. Giotto was the one to fly closest to Halley’s comet thus becoming the first space probe to provide an image of the nucleus of a comet. Not many people know that! It survived the encounter and was still intact in 1992 when it was woken up to transmit data as it did a fly past of another comet.

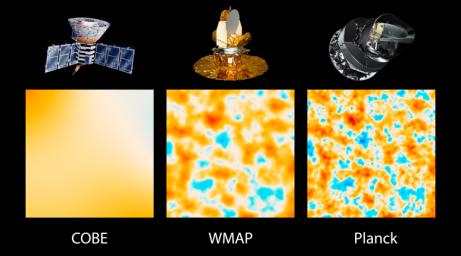

The next mission Paul mentioned was the XMM Newton satellite (X-ray Multi-Mirror Mission) launched in 1999 and still producing great results, see http://sci.esa.int/xmm-newton/ for details. The Herschel and Planck Space Observatories were launched at the same time in May 2009 though they are now operating independently. Herschel is the largest telescope in space with a mirror 3.5 metres across and it is getting results by looking at far infra-red wavelengths. Planck’s forerunners were COBE and WWAP, looking at Cosmic Microwave background, and it has achieved much higher resolution as shown in the comparison of images from the 3 generations of satellite.

The story I liked best was of the Huygens probe which was launched from the Cassini spacecraft to land on Titan, the major moon of Saturn. Like Rosetta, this received a huge amount of publicity at the time. What didn’t get much attention, much to Paul’s frustration, was the fact that the Department of Physical Sciences at the Open University at Milton Keynes had a leading role in designing the Surface Science Package on behalf of the ESA. This was a suite of nine sensors that has been designed to record details of the probe’s landing site. The principle instrument was an external accelerometer which measured the force with which a sensing ‘spike’ stuck the ground, and the resulting data revealed the physical properties of the pebble covered “soil” of the landing site. So in a sense, a part of Milton Keynes is now part of the Titan landscape.

It was hard to imagine Paul getting even more enthusiastic about a particular space mission but he nearly went into orbit himself when he started talking about the Gaia Space Observatory, an ambitious project to map and catalogue up to 1 billion objects in the Milky Way. At present, in Paul’s analogy, if we think of the Milky Way as being the size of a room, then we only really know about a region roughly the size of a dinner plate around us. Gaia will transform that ! Not only will it increase the amount we know but the accuracy with which we know it. Resolutions are quoted in micro-arcseconds.

The most memorable part of the evening was seeing the props Paul had brought with him. He normally makes his presentations to school groups and he described the “Wow” reactions of both primary and secondary pupils to what he was demonstrating. Our reactions were about the same! He showed us fuel igniting in a large bottle to model rocket action. Did we want to see it again? Of course we did! Then it was how a piece of chocolate embedded in a giant marshmallow can survive having a blow-torch directed at it, as a model of how ablation, for example of the Shuttle tiles, can protect astronauts during re-entry. And a few of us could not resist the opportunity of trying on a replica spacesuit.

By Katherine Rusbridge

Image Credit: Danny Thomas

Image Credit: Danny Thomas

Image credit : Danny Thomas

Talk given by Paul Hill from ESA

Post written by Katherine Rusbridge

Aug 2016