I am often amazed by the knowledge, skills and commitment of the so-called amateur astronomers who give presentations to us at our monthly meetings. An excellent example of this was when we welcomed Tim Haymes who gave a very engaging talk about observing occultations. Now, one of my top “Wow” moments is from a few years ago when I watched Saturn through a small telescope being occulted by the Moon (ie the Moon moved slowly in front of Saturn to obscure our view of it). It was the dark limb of the Moon which did this so the rings of Saturn just seemed to disappear for no obvious reason, followed by the rest of the planet. It was a wonderful sight but I didn’t realise there is more, much more, to observing occultations than the simple visual “Wow factor”.

Tim gave a brief overview of occultations and reminded us that an occultation is when one body moves between a more distant object and us so that the light from the further one is blocked. It is the further one which is described as occulted. It is called a lunar occultation when the body “in the way” is the Moon. The Moon can occult a planet though this is fairly rare and it can also occult any one of over 3500 stars which are in the ecliptic plane. These days, occultations are monitored not just by visual observation but by recording light intensity as a function of time which can reveal extra detail. For example in some cases, there is a drop in intensity, followed by a further drop in intensity, revealing the fact that the “star” is in fact a binary star.

More intriguingly, Tim spoke of his contribution to observing occultations by asteroids of distant stars. These occultations last only seconds because of the small size of the asteroid. It is definitely a case of “blink and you’ll miss it”. Tim is a part of a community of enthusiasts who aim to combine their results from a given event to allow the shape of an asteroid to be deduced. To understand how this is possible, think about the information available about solar eclipses. We are told the track of totality and what time we could expect first contact at various places. Similarly, though with a greater degree of uncertainty given how small an asteroid can be, a path is predicted for observing the occultation of a star by an asteroid. Observers across that track then record and report the exact timing and duration of what they see as well as their location. If one observer sees a short duration occultation, it must mean that he or she saw a small cross-section of the asteroid pass in front of the star. If an observer sees a longer duration occultation, he or she saw a larger cross-section of the asteroid pass in front of the star. Combining the results tells us the shape of the asteroid. (One of the first occasions when this was used was used during an occultation by the asteroid Eros and the results helped to determine its shape). This is all explained much better and with diagrams by Tim himself at http://www.stargazer.me.uk/start.htm . It seems amazing that this can be done using a lot of skill and patience but not particularly sophisticated equipment by enthusiasts in their back gardens.

Tim also told us about some of the special results found by studying occultations. Did you know that the rings of Uranus were discovered by two astronomers who had set themselves up to observe the occultation of a star by that planet? When they looked at the light intensity pattern, they saw the expected dip as the star was occulted but either side of this on the time-scale were four short-lived reductions in intensity with the pattern in the lead-up to occultation being exactly the same as the pattern immediately afterwards. Something else symmetrically arranged either side of the planet had caused the “mini-occultations”. Conclusion : Uranus has at least 4 rings.

Grazing lunar occultations are another intriguing phenomenon. Here, a star appears to just skim past the Moon. (In reality it is the Moon which moves relative to the star). The details of what is seen will be affected by the landscape of the Moon at that point, with the star seeming to blink as it disappears behind mountains and reappears in the valleys. Again, this seems to me to be an amazing observation to be made from Earth and is one which, I think, amateur astronomers have been able to make.

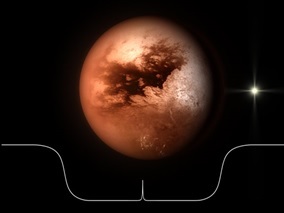

One more result which impressed me came from the occultation of a star by Titan, the largest moon of Saturn. The light intensity pattern gave the expected sharp decrease, signalling the start of the occultation with the intensity recovering to its original level as the star emerged. There was an extra in the form of a central spike in intensity! (see artist’s impression below)This is explained by the presence of Titan’s atmosphere refracting the star’s light.

Returning to Tim’s main theme of asteroid occultations, if you want to try to catch an asteroid occultation, then you might have to wait a bit. There are none predicted for UK during the rest of 2015, see http://www.asteroidoccultation.com/2015-Best-Events.htm . Peru and Mexico seem to be the places to visit. We have better luck in 2016 according to this website : http://www.stargazer.me.uk/call4obs/Predictions_2016.htm So good hunting!

If you are really keen on finding out more, type “Lunar Occultations Nasa” into Google and select “The complete guide to observing lunar, grazing and asteroid occultations”. The author isn’t kidding when he says “complete” – the document is 379 pages long. It includes everything you need to know and a lot more besides. The part I skimmed through reflected on the fact that you often have to travel away from home to get to the predicted path for observing an asteroid occultation. This led the author to offer some marriage guidance advice and this top tip (which I paraphrase) : “don’t antagonise the locals by cutting down trees to give yourself a better view.”

Talk given by keen amateur astronomer Tim Haymes

Post written by Katherine Rusbridge

April 2015