Finding the Winchcombe meteorite

It is the dream of every meteor-watcher to help retrieve a meteorite – ie a meteor which actually makes it all the way to the Earth’s surface. UKMON, a meteor-monitoring group set up by two Farnham Astronomical Society members, did just that in February 2021 playing an important role in locating what is now known as the Winchcombe Meteorite. This was the topic of our talk in February 2022.

About UKMON

Before we get to the Winchcombe Meteorite, here is an introduction to UKMON. It was set up by Peter Campbell-Burns and Richard Kacerek in 2012 , each of them having a camera looking up at the night sky. Back then, it was a daily task to look through all the recordings to see if any meteors had been captured and manually processing any interesting observations. This has now grown to a network of 100 cameras all over the country, including on the Natural History Museum. Each camera is linked to a Raspberry Pi Meteor Station which does all the processing automatically and sends an email of results to all observers each morning.

Image Credit: Mary McIntyre

A key goal for the network is to identify any meteor which was recorded on more than one camera. The images can then be processed together to identify the trajectory of the meteor and it may be possible to extrapolate this data to find out where it originated from … and also where it may have landed!

Finding the Winchcombe Meteorite

It is one thing to be able to judge the trajectory of a meteor; another thing to predict where it lands. This is because the incoming object burns – ie is seen as a meteor – as it passes through the atmosphere from a height of about 115km to 90km. It then continues in dark flight until it hits the ground, or as is more likely on Earth, it splashes down in water and is lost forever.

On the night of February 28th 2021, the world of astronomers got lucky. A sonic boom was heard in southern England and there were about a thousand eye-witness accounts of seeing the meteor – and of course, it was captured on several of the UKMON cameras.

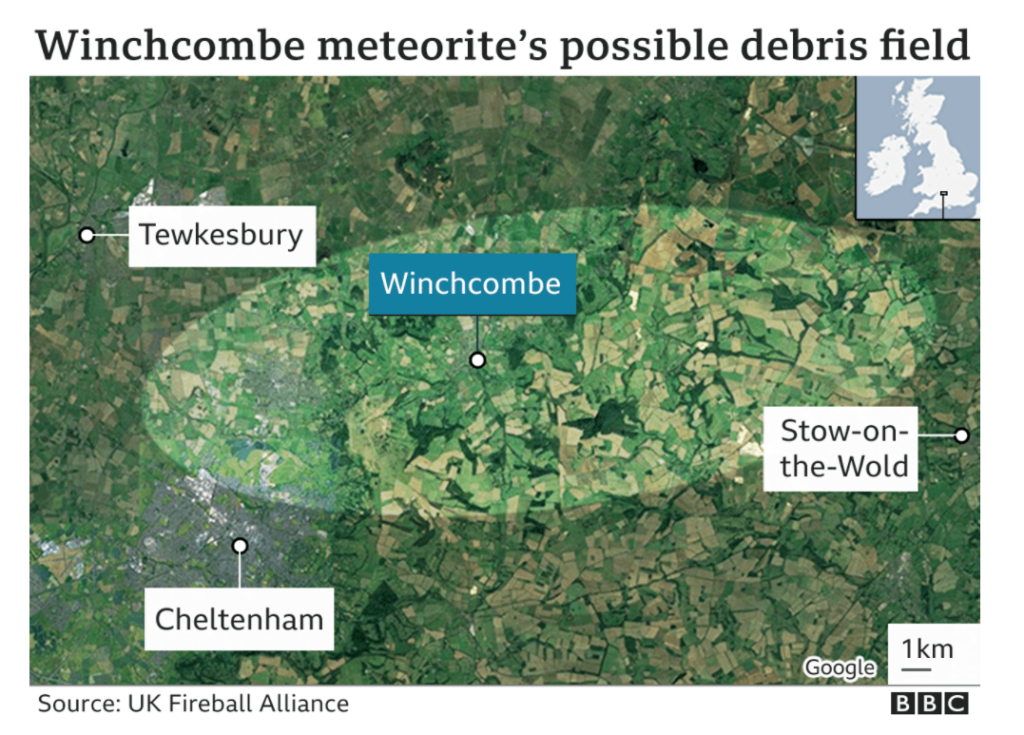

UKMON are part of the UK Fireball Alliance, consisting of six groups of camera networks. All their data was combined by academics to pinpoint Winchcombe as the most likely area for the meteorite to be.

Image Credit: BBC, UK Fireball Alliance

Famously, part of the meteorite was found on the driveway of a Winchcombe family, though it had mainly disintegrated on impact. Given the level of publicity there had been in the media, they knew exactly what to do in order to retrieve the sample without contaminating it. Within 12 hours, it was safely bagged, collected and on its way to the Natural History Museum.

Image credit: NHM

A real “feather in the cap” for all the amateur astronomers in the UK Fireball Alliance, including UKMON and a brilliant illustration of the value of collaboration between academics and amateurs.

A few footnotes

Peter in his talk compared the cost of acquiring the Winchcombe meteorite with the cost of two missions which collected samples from space and returned them to Earth for analysis. The Hyabusa mission returned with tiny grains of material from an asteroid at an estimated cost of $100million for each gram of material. The Stardust mission collected samples from a comet at an estimated cost of $199million for each gram of material. The Winchcombe meteorite yielded over 500 grams of material, once all the surrounding area had been investigated, for the cost of a few return railway tickets.

And the fact I liked most :

The indented section of the family driveway where a chunk of the meteorite had landed was cut out and is now in the Natural History Museum

Useful links

UKMON homepage

How to use a Raspberry Pi Meteor Station

This is written by Mary McIntyre,an outreach astronomer and teacher of astrophotography based in Oxfordshire, UK. The image of the camera is taken from her article

Talk given by FAS member Peter Campbell Burns co-founder of UKMON

post by Katherine Rusbridge

March 2022